ONE MORE JAUNT THROUGH THIS WILD DECADE

As this is 1970's month, that's my focus. Jake and I like to poke fun at Joe Morgan, a key member of the Big Red Machine in Cincinnati that won a couple World Series titles in '75 and '76. When he did commentary for baseball games on ESPN, old Joe would invariably compare the game in the present day to the 1970's, and he always ended his argument with, "things were tougher in the 1970's." So, that became our rationale for not complaining about hardships. My students are baffled when I say it out of habit. I wasn't alive in the that decade, so what do I know? Thanks to deep insights from the likes of Joe Morgan, I don't need to have lived it. I already know it was tough. Sure, Joe. Whatever you say.

|

| .819 OPS, 689 steals, 2 MVPs, 1 scrambled brain |

BUT WAIT, HE MAY BE RIGHT

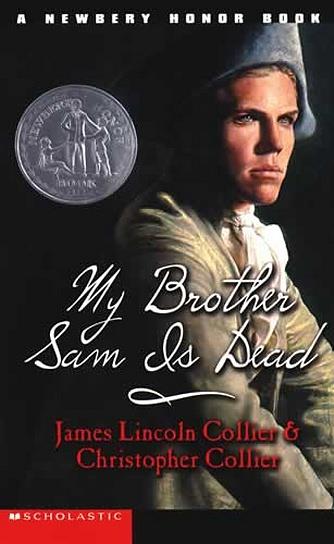

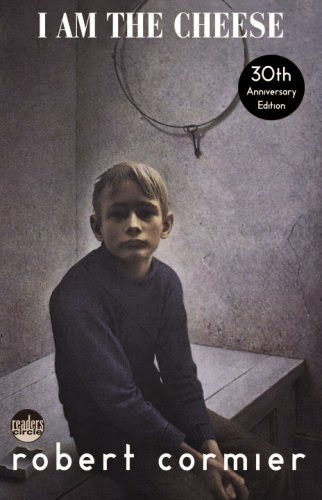

Lest you think he's full of it, Joe has a point. Aside from the brutal Astroturf, suffocating polyester jerseys, and slap fights in the clubhouse, Morgan did play baseball during turbulent times, and as we all know, those social conditions are usually reflected in the literature. I Am The Cheese is a crime novel, but it centers on a socially awkward youth who is institutionalized and being used by the government; My Brother Sam Is Dead reflects the unrest and political upheaval of the 1970's through the lens of the American Revolution; even the timelessness of The Princess Bride ends on a question: do they live happily ever after? I don't dare read any Judy Blume books from this decade; it's been a long time since I was a 13-year old girl, and I'd rather not spontaneously turn into one after reading Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret.

Add to this litany of realistic (read: sad) endings the YA novel Hey, Dummy, which is a hot mess from start to finish. In a scant 168 pages, author Kin Platt confronts: mental retardation (his term, not mine), autism, bullying, abusive parents, poverty, racism, the Chicano movement, societal prejudice, failure of the public school system, and a toy drum. There's a dead brother who figures in for about nine seconds, too. WHAT. THE. I colored these red because every time I think about this book, blood shoots out of my nose.

My first reaction to this book: What did I just read? THIS IS TERRIBLE. It's preachy, jumbled, over-dramatized, simplistic, yet completely out of control. That's the review I wanted to write before I realized I had a brain and a nuanced understanding of history, guaranteeing that I will never land a job on a cable news network.

|

| More like, Hey, Drummy. |

So, let's consider the contemporary context of this book, which was published in 1971: the black rights movement continues after MLK is assassinated in '68, the Chicano movement is unionizing farm workers and organizing in cities where their neighborhoods had been ripped apart for interstate highways (and infamously, Dodger Stadium), women's rights, Indigenous Americans occupying Alcatraz, the "war" in Vietnam is going poorly and public opinion is turning against it, police brutality at the Democratic Convention in '68 still fresh in the public mind, compounded by the Kent State shooting in 1970. And this was a time when people couldn't escape with pictures of cute cats on the internet. JOE MORGAN WAS RIGHT.

This time period itself was a mess, and I think this book reflects that. Neil Comstock is a fairly normal 12-year old boy who bullies a new kids in town, and afterwards realizes the boy (Dummy) is mentally retarded. That's the language used in the book; I realize that the stigmatization of this term has led schools to use other terminology in recent years. Neil writes a short paper in class about his experience with the Dummy, and is lectured by his teacher, Mr. Alvarado. Neil feels remorse for his actions and later defends Dummy against bullies in his school, which soon costs him his own friends. Slowly, Neil begins to examine the world as the Dummy does, and at this point I'm thinking this is an after-school special with warm fuzzies and everyone loving and understanding one another. WRONG. Read on.

|

| A typical sight in 1970. Supposedly, the English/Philosophy building where I went to college was built of solid concrete to be "riot-proof" - it was also air-conditioning proof. On 80-degree days the EPB was a balmy 130. We were too sleepy to riot. I've never seen a riot-proof engineering building. Conformist nerds! |

Alvarado is the voice of wisdom in this book, but also the hackneyed preacher. Comstock visits Alvarado for advice on the Dummy, and gets the speech about how people fear what they do not know, which creates hatred and blahblahblah we've heard this all before. Thanks for stuffing the moral of the story in my eye sockets. Strangely, this is preceded by Alvarado telling Neil EVERY PRIVATE DETAIL about the Dummy. FERPA may not have become law until 1974, but Alvarado, who is supposed to be this moral compass, just violated the privacy of the Dummy and could easily lose his job by breezily telling Neil all about this troubled boy's background and his sister's autism, which is explained away as her needing drugs and treatment or she'll always be that way. [PAUSE] This is all there is to the autism discussion. No more. Nothing from the perspective of the person with autism, or say, anyone who thinks that drugs and treatment are not the answer. Boom. Drugs. The short shrift to these issues is not exclusive to autism, but is the most glaring example. For a much more thorough discussion of autism spectrum in YA literature, read the excellent Al Capone Does My Shirts. [RESUME]

THEN, Alvarado explains how the state of California (in 1971) categorizes mental retardation (author's words, not mine) and that many schools do not have appropriate programs for these students, and let them rot in classrooms with younger students. WHY AM I READING AN EDITORIAL IN THE MIDDLE OF A NOVEL. Probably because this is how the time period went: propaganda everywhere; rhetoric all over the place, and the push to bring social injustice to light. What's most fascinating is how Alvarado guides Neil to understand the Dummy and get involved. Then, when the Dummy is accused of murder and a bunch of villagers with pitchforks and torches come after him (don't ask) Neil takes him to Alvarado for safe keeping, and Alvarado screams about how harboring a suspected murderer will cost him his job (oh, but sharing private information won't) and set back the Chicano movement in Los Angeles. YES! COMPETING VALUE SYSTEMS. He goes from "we must understand this person and his unique situation," to "get him the bleep out of here, only the authorities will know if he is capable of killing someone. I have to protect the Mexicanos and our tenuous hold on anything resembling rights." NIMBYism in action.

All this time, Neil is dealing with lousy parents who seemingly hate him and his kid sister; they verbally abuse him and slap both kids on a couple occasions. They're flat characters, but this kind of domestic situation is hardly rare, so I'll reserve any complaints about the parents; their hollering against Neil suggesting that he bring the Dummy over for a visit because he's a "misfit," and "moron," and could harm Neil's sister serves the story and probably represents the views of many who, as Alvarado says, just don't understand. HOWEVER, the dead brother part seems tossed in to exacerbate Neil's issues with his parents. The dead brother is mentioned in passing at the beginning of the novel, and then returns when Neil weights his relationship with his parents in a soliloquy to the Dummy; he somehow has a memory from his infancy in which his father states that he preferred Neil had died. THAT is the point I almost chucked this book. All of this commentary on the state of society and your turning point is the realization that his dad wanted him dead based on what is probably an invented memory. Kin Platt, you just threw away what could have been a brilliant book, and then had an elephant crap on it by having Neil take on the persona of the Dummy because it's "easier." Even for a 12-year old, that kind of thinking is dangerous and off-putting. This book was about the plight of the mentally handicapped, until it drove Neil bonkers. Why is the protagonist going insane? WHY DOES EVERY BOOK FROM THE 1970s END WITH A KID GOING TO THE NUT HOUSE.

AAAAAAAAAAARRRGGGGGGGGHHHHHHHH

Okay. I'm better. There is a decent, but manufactured reason, that Neil ends up institutionalized, but it is out of left field and not seemingly related to the thousands of themes presented in the narrative. Which, I suppose demonstrates the random acts of senseless violence that plagued the era of this book. The social issues discussed firmly plant the book in 1971 and the surrounding years, but the story, which I believe to be portrayed as realism, becomes so wild and increasingly irrelevant that it loses me.

FINAL VERDICT: Not much literary value, but stands as a view of a complicated era, and might be used in some historical context. Very much a novel of its time, when things were tougher. Just ask my pal Joe.

That is all for the 1970's. I can't take it anymore. I need to read something not so depressing. Why not an alien-human love story?

NEXT TIME, I YELL ABOUT

A free e-book that I sort of promised the author I'd review. Let's just say that this story is inspired by the show Ancient Aliens, which means it'll probably be a HAIR-RAISING EXPERIENCE!

|

| ^ that's the joke. |

BORING STUFF

Kin Platt

1971 Chilton