|

| I've read 3 of these 5 books, so I'm qualified to whine about them all. |

LOOKING FOR PAPER TOWNS

Doesn't matter who the author is - read more than two of their books and you'll see their patterns. This is not a criticism, but an observation. Here are a few I've noticed:

TC Boyle: uses words nobody else knows. Probably owns a thesaurus the size of a bread truck.

John Grisham: Always with the lawyer crap.

Vonnegut: Can't help but insert himself, or elements from his own life, into his stories

Tolkien: Nothing like reading about singing dwarves

Stephen King: Lots of boring things happen, then something scary happens. Repeat.

Gertrude Stein: Completely insane.

I repeat: THIS IS NOT A BAD THING. These patterns reveal much of the author, and despite

+John Green's attempt to dissuade us from divining anything about the author from the fiction they write as dismissing the merit of the novel itself* (spoiler alert: wrong!) we can learn much about him as a writer, when comparing

The Fault In Our Stars to

Looking For Alaska and

Paper Towns.

*When Green asks his readers not to attempt to look for hidden meaning in the story, guess what? They're going to look for hidden meaning in the story. "I made it up" is not enough to convince anyone that he's inserting something about himself for us to find. And to say this diminishes the impact of the story itself, and that fiction doesn't matter if we look beyond the page to the author? I don't completely buy it. There is such a thing as compartmentalization, a capability most likely possessed and practiced by the "smart people" about whom Green prefers to write.

AN ABUNDANCE OF FAULT

I was going to scream and holler about how these books are all the same, but

Green has already addressed this on one of his many web presences. So, we'll examine his own words on the matter.

The Fault in Our Stars is very different (it’s narrated by a girl; she is not in high school; her concerns are somewhat different from the concerns of my previous protagonists; etc.)

When quibbling differences in gender narration and school status (a 16-year old part time community college student as opposed to a high school student - big whoop) are what separate your books and make them

very different (a word, by the way, that good writers know to avoid), you've got trouble. I accept the concerns argument, as the male narrators of the previous two novels tend to only suffer from debilitating social communication problems, rather than a terminal illness. This speaks to his larger point of exploring the Romantic Other, which is a fascinating concept, and what puts him on a shelf above most other YA authors:

A lot of people read [Paper Towns] as a rewriting or a revision or a revisiting or whatever of Looking for Alaska, which is totally fine (books belong to their readers), but to me it is the complete OPPOSITE of LfA (one is about the legitimacy of Great Lost Love, and one is about the absolute ridiculousness and illegitimacy of Great Lost Love), or at least that’s what I intended.

No quarrel here. The thematic adjustment between the two is plain to see, and I think that Green puts another spin on Great Lost Love in

Fault, which is to consider one's legacy after they've passed on, and what lies on the other side. Will the Great Lost Love be requited in the afterlife? Will it continue to live forever in the hearts of those still alive? By the way, Hazel's meditation on these sentiments that we seem to casually toss out when someone dies was fantastic. One of Green's strengths is deconstructing the everyday (or, as reviewers like to say, quotidian) phraseology of our culture and adding the right amount of cuss words to make us think, "yeah, screw that!"

That said, If you have to spell it out for your audience, maybe they're not that smart.

(I also like smart people who do not find irony a convincing way to hide from intellectual engagement, which is the A#1 reason I like writing about teenagers.)

Damn.

Katherines seems to me wholly different from my other books except in some uninteresting superficial ways (like, it also contains a road trip, and it also contains a romance and nerds, but those are boring and trivial similarities...

Whoa there, buddy. You just named boring and superficial differences between

Fault and your other books to argue that they're

very different, while pointing to trivial similarities as unjustifiable criticism.

In the end, Green knows the pratfalls of explaining his books - the relationship between author and reader is ever tenuous and subject to too much filling-in by the reader, whose individual interpretations will trump any point the writer tries to make. Such is the nature of perception. And, to an extent, personal relationships.

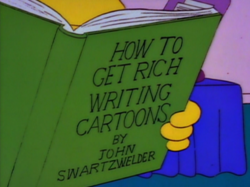

|

| The reason most men are still boys. |

THE STARS ALIGN

As for The Fault In Our Stars as a book on its own, I say this is Green's best. He's at his best when writing through the rawest of emotion that his characters must experience/suffer; it's lyrical without being schmaltzy and pedantic, tight, lucid, cogent, and other 25-cent words that would make Hazel Grace like me.

This one took a while to get going, but the sustained intensity of the last half of the book cannot be denied. With Paper Towns, we're thrown right into Margo's magical night and disappearance (see, they're very different). Here, we have to slog through significant exposition before the story really kicks in - naught but a minor complaint about the pacing.

The themes of this book: love the one you're with, leaving a legacy, what happens after we die, are all folded well into the narrative. The inclusion of a book-within-a-book device makes the metaphor more obvious; Hazel wants to know what happens to her favorite characters after a book ends. Yes, the afterlife of a fictional character. Do they find love, what happens, does anything happen? Just as we're unsure of anything after passing from this mortal coil, Hazel needs some kind of reassurance about these characters to whom she's married her own personal hopes.

Selfishness plays a hefty role in this book. Each character deals with their own short-sighted wants, and they manifest in shouting matches, avoidance, and lots of crying, as most selfishness does.

About Van Houten: Clean-cut author with massive internet presence writes about boozy a-hole recluse writer who refuses to read fan mail. Green must have had fun with this character. I'm digging for fact within fiction, which is a no-no, but I bet he had to make Van Houten an American so that the Dutch fellowshop he received would come through. Not to dismiss the power of storytelling, or anything.

For all that's wonderful and moving about this book, he reduces his characters to near-stereotypes. Augustus plays video games and reads novels based on video games. Hazel watches America's Next Top Model and likes to be catty about it. Trivial, surface similarities, sure, but come on, branch out. I say this knowing that most readers enjoy the comfort of predictability, which is why there are so many book and movie series that recycle characters and plot lines and make millions of dollars.

But here’s the thing: I am not the only writer. There are many, many writers creating a huge variety of stories—tens of thousands of novels will come out in 2012, for example—and it’s not really my responsibility to tell every possible story. I can only tell the truest versions of the stories I know, so that’s what I’m trying to do.

Amen, brother.

JOHN GREEN, JOHN GREEN

The John Green Book Checklist

- Young protagonist with ample vocabulary - word placement screams thesaurus

- Enigmatic love interest

- Statement about the attractive nature of curvy girls

- Protagonist reads and continually refers to "classic" works of literature that no one reads anymore, but the characters create meaning from them to apply to their own experience

- Death (or presumption of death) is the main catalyst for action

- Jovial and loving parents who remain flat characters (exception: Fault explores the parental relationships more in-depth)

- A character who goes by their full name

- Protagonist thinks s/he is nothing special, but finds through his/her adventure to be capable of the extraordinary

Follow these simple steps and you too can have a New York Times Bestseller! I think there's an element of teenage fantasy fulfillment in his writing, which is fine; that is where most, if not all, writing begins. However, he doesn't want me to talk about it, and if I do, a bunch of nerdfighters might beat me up with words, so I won't. Suffice to say: all three books satisfy, are uplifting in the face of losing someone forever, and Green acquits himself well as to character motivations in his own commentary, but I'll continue to divine fact from fiction just to get his goat. Because, you know, word of this will get to him. /Sarcasm.

NEXT TIME, I YELL ABOUT

Another John who has a formula and sticks to it. These probably aren't meant for young readers, but they're funny as hell and they read fast & easy. Let's just say what the cover of every one of his books says...

BY THE WRITER OF 59 EPISODES OF THE SIMPSONS!

BORING STUFF

The Fault in Our Stars

John Green

2012 Dutton Juvenile